Chapters

1 – Stone Lithography

2 – Offset Lithography

3 – A poster is not just a lithograph

4 – What is an “original” poster

5 – Linenbacking explained

Part 1 – Stone Lithography

“

Lithography was invented in 1798 by Aloys Senefelder. The process is founded on a simple principle: oil and water do not mix. To begin, the artist works on a carefully prepared block of limestone (“lithos” meaning stone). Not every stone is suitable — only the fine-grained limestone from the Bavarian quarries where Senefelder first developed the method has the right properties.

On this surface, the artist creates an image using a greasy lithographer’s crayon or a stronger medium known as tusche. Tusche can be applied with a brush like ink or with a pen, allowing for a wide variety of textures and effects. The drawing thus formed becomes the basis for the chemical process that allows the stone to accept ink in some areas and repel it in others.

Lithography is distinctive among printmaking methods because it allows the artist to draw directly and freely onto the stone surface. This immediacy makes it especially appealing to artists from other disciplines who may not typically work in printmaking.

Once the drawing is complete, the stone undergoes a chemical treatment that fixes the image securely. During printing, the areas containing grease from the lithographer’s crayon or tusche naturally repel water, while the untouched areas of the stone absorb it. This precise balance of grease and moisture enables the ink to adhere only where the artist intended, faithfully transferring the drawing to paper.

The result is a print that captures the spontaneity, subtlety, and full range of the artist’s hand — qualities that make lithography one of the most expressive forms of printmaking.

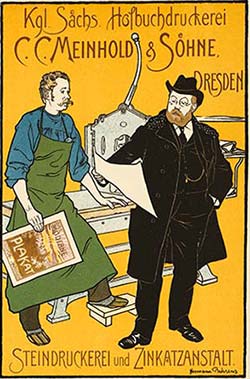

Master Lithographer painting on limestone

In the next stage, the stone is carefully cleaned with turpentine or a similar solvent, which removes the visible traces of the artist’s drawing. From this point onward, the image is no longer apparent on the stone’s surface — it exists only in the chemical balance created between grease and water.

When printing begins, the stone is first dampened with a wet sponge. The moistened, grease-free areas repel the oil-based ink, while the portions previously drawn with greasy crayon or tusche reject the water and accept the ink. In this way, the stone selectively takes ink only where the artist intended the design to appear, leaving the remaining areas as clean white space.

This delicate interplay between ink, grease, and water is the essence of lithography. It allows for an extraordinary fidelity to the artist’s original drawing, preserving every nuance of line, shading, and texture.

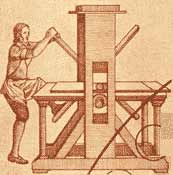

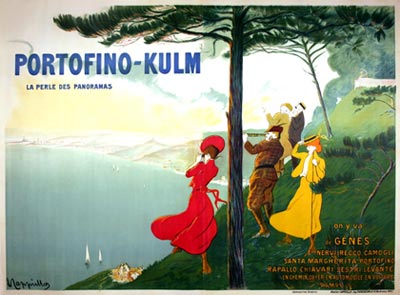

Leonetto Cappiello at Vercasson Imprimerie working on a limestone

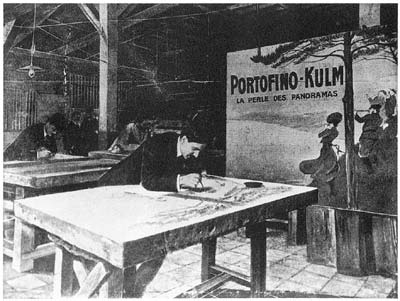

3 Color passes from the Stones used to make the final image (upper left)

Above is an example of a finished plate reproduced from Das Moderne Plakat. The image in the top left shows the final result, created using only three stones — with no black ink employed. Instead, the colors are achieved through layering: yellow and blue combine to produce green, while blue and red together create the lavender of the robe.

The richness of lithography lies in these overlapping tones. By varying the combinations and the intensity of ink applied, the printer can produce a wide spectrum of colors. The white paper itself serves as the background, adding lightness or depth depending on how the inks are layered. Each color requires its own pass through the press, with the sheet dried carefully before receiving the next layer.

This method demonstrates the precision and artistry of lithographic printing, where a limited number of stones can generate a striking and complex final composition.

The printmaker next employs a lithographic press to transfer the inked image onto paper, pressing the sheet firmly against the stone. Unlike copper plates used in etching, lithographic stones do not wear down with repeated use, allowing the process of wetting, inking, and pressing to be carried out many times. This durability made lithography especially valuable for producing multiple impressions of the same design.

Beyond its practicality, lithography is renowned for its artistic range. It can generate both bold, solid areas of color and delicate gradations of shading, qualities that attracted painters such as Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec, who embraced multicolor lithography to make his art widely accessible.

For each color in a composition, a separate stone must be prepared. The paper is then carefully registered and aligned for each successive pass through the press, ensuring that the different colors combine precisely on the final sheet. This meticulous layering of colors is what gives lithographic posters their richness and vibrancy.

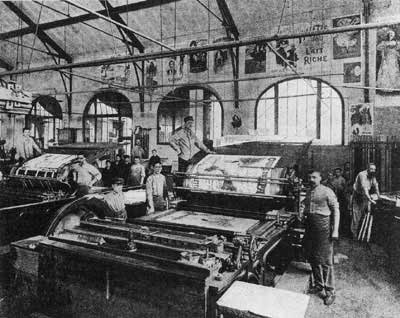

Posters rolling through presses c 1920's

Part 2 – Offset Lithography

Another related method is drypoint, in which the maître-imprimeur or artist lightly etches the design into a metal plate, much as one would prepare the surface of a lithographic stone. In this case, however, the work is done on zinc plates, with a separate plate required for each color. The artistic result can closely resemble that of stone lithography, offering similar richness and depth of line.

In the earliest presses, these plates were used flat. Later, for greater efficiency and larger production runs, the plates were adapted to fit around rotating drums, allowing paper to pass continuously through the press. This evolution paved the way toward more industrialized printing methods, while still retaining many of the artistic qualities of earlier lithographic techniques.

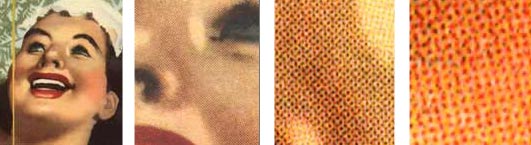

A "blowup" of a "quadrichrome" or 4 color offset lithograph section, circa 1950 Italian. Note that the dots are "mechanically" aligned to blend together to create a complete spectrum of color using the white backround as part of the blend.

Offset lithography often begins with a photograph or digital scan of an artwork — whether an original painting, a gouache, or another image. In the pre-press stage, the image is separated into the four fundamental printing colors: cyan (blue), magenta (red), yellow, and black. Traditionally this was done with a special camera, while today the process is handled digitally by computer.

From each color separation, a negative is produced. In the print shop, these four negatives are used to create four corresponding printing plates. Unlike traditional stone lithography, the images on these plates consist of photo-mechanically spaced dots (the halftone process). When printed in precise alignment, the overlapping dots of cyan, magenta, yellow, and black combine to reproduce the full range of tones and colors in the original image.

"Industrie Grafiche Moneta" of Milano, an important offset printer in 1950. This machine gives you an idea of what offset lithography looked like at the time. Notice the posters being printed for "Coca Cola" and the many movie posters on the wall.

The plates are then mounted on a four-color press, where all four inks are printed in a single pass. When examined under a magnifying glass, prints produced in this manner reveal their structure: the four standard inks appear as evenly spaced dots, arranged in precise rows. This pattern is the hallmark of photomechanical printing, clearly distinguishing offset lithography from traditional stone lithography.

In practice, nearly all publicity posters created in France and Italy after the Second World War were produced by this method. From Gino Boccasile’s Lauro Olivo to Cassandre’s Venezia, offset lithography was the process that defined the poster art of the postwar era.

2003 Modern Heidelberg Speedmaster (5 colors)

Part 3 – A Poster is not just a Lithograph

Lithography was not limited to stone. By the early 20th century, images were increasingly transferred onto metal zinc plates. These were first used flat, but soon adapted into curved forms mounted on drums, allowing paper to be fed continuously and enabling much larger print runs.

An early development of this technology was chromolithography, invented in 1835 by Godefroy Engelmann, which used multiple stones or plates to build up rich color images. By the time of the Second World War, zinc and aluminum plates had become central to a new process — offset lithography (described above). In this method, at least four drums carried the primary colors, printed in precise layers of photomechanical dots against white paper to produce the full color spectrum.

At the outset of World War II, these dots were relatively coarse and easy to see. Over the following decades, improvements in technology reduced their size dramatically. By the 1950s, the dots had become much finer, and today they are so small that they may only be visible under magnification. Modern presses, such as the large Heidelberg offset machines, can even achieve ten-color printing without relying on visible dot structures, producing images of exceptional clarity and depth.

Part 4 – What is an “Original Poster”

Posters can be created using virtually any printing method — serigraph, stone lithograph, offset lithograph, woodblock, or silkscreen — and on a wide variety of papers. At its core, a poster is a form of publicity, designed to announce, promote, or call attention to something.

The range is vast: a primitive woodblock or early Gutenberg press calling townspeople to “stone the thief” in the town square; a small revolutionary press distributing leaflets urging Russians to rise against the Czar; a stone lithograph by Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec inviting Parisians to the Moulin Rouge; or a 1950s offset lithograph by Gino Boccasile advertising Lauro Olivo soap.

Regardless of artistic merit or printing technique, what defines a poster is that it was the original printing for an event, product, or cause, intended for use at the time. Some campaigns were so successful that advertisers reprinted the same design for decades. A famous example is Cappiello’s “Thermogene,” which remained in use for nearly half a century, reissued by different printers in multiple countries and years. All such printings are considered valid collector’s pieces, because each was produced by or for the advertiser as part of its original publicity purpose.

rare Cappiello stone lithograph

he image was derived. Instead, the poster represents a method of reproducing that image in quantity for public display.

At the turn of the 20th century, stone lithography required far more manual skill and artistry, and printing runs were often smaller. Artists such as Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec even worked directly on the stones themselves, experimenting not only with the image but with the boundaries of the process.

That said, a stone lithograph is not inherently more valuable than a 1950s offset lithograph by a recognized artist. Value is not determined by technique, but by demand — which can be shaped by many factors: the artist, the subject matter, the place or product being advertised, the rarity of surviving examples, and the overall condition.

For this reason, collectors are best served by working with an experienced professional, who can provide guidance and trustworthy advice when considering poster purchases.

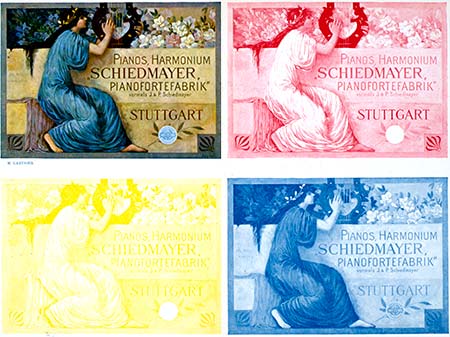

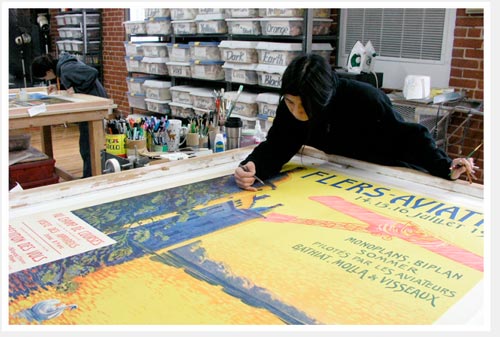

Poster Conservation of Stamford Connecticutt, where we can see top quality linenbacking in progress. The Aviation poster has been put on linen and is stretched on a frame. In the back another poster stretched on to a frame is being restored. The Girl in the foreground is using water soluble gouache crayons, respecting museum quality archival preservation of the poster.

Part – 5 – Linen-Backing explained

Professional poster dealers specializing in antique and vintage works will almost always preserve their posters through linen-backing. This archival method mounts a poster on a canvas support, giving it strength and stability.

The process begins with a professional linen-backer stretching artist’s canvas tightly over a frame, much like preparing a painter’s canvas. A sheet of smooth watercolor paper (canson) is then applied with a reversible, water-soluble, acid-free adhesive containing anti-fungal properties. Finally, the poster itself is mounted on top with the same glue. These steps prevent yellowing, acid damage, and humidity-related fungus over time.

Because canvas, paper, and poster dry at different rates, the work must remain on the frame for several days (sometimes a week or more) until it is completely dry. This careful drying avoids buckling or warping.

Linen-backing not only preserves fragile paper but also protects against accidental tearing and folding. It provides a safe handling margin — usually two to three inches of the white watercolor paper — so framers can secure the piece without touching or gluing the original poster. This safeguard is critical, as improper framing can significantly reduce a poster’s value.

Not every poster requires linen-backing. Old or delicate examples benefit most, while many contemporary posters in excellent condition can be framed directly. Some very heavy paper stocks are unsuitable for lining altogether. For that reason, it is always best to ask about linen-backing when purchasing a vintage poster.

Part – 6 – Authenticity

Many dealers and sellers of vintage posters claim to provide Certificates of Authenticity, and some even suggest you should not purchase a poster without one. In truth, however, a certificate can only be legitimately issued by the original printer or the artist, confirming that the work is their own. Only they can certify, beyond doubt, that they printed or created the piece.

Any other certificate is essentially a statement of opinion from a dealer. Its value depends entirely on the credibility and expertise of the individual issuing it, and therefore holds no independent authority or universal meaning.

What truly protects a buyer is a detailed receipt or invoice from a reputable dealer or society, clearly describing the poster — including the artist, printer, and date — so there is a reliable written record of exactly what has been sold.